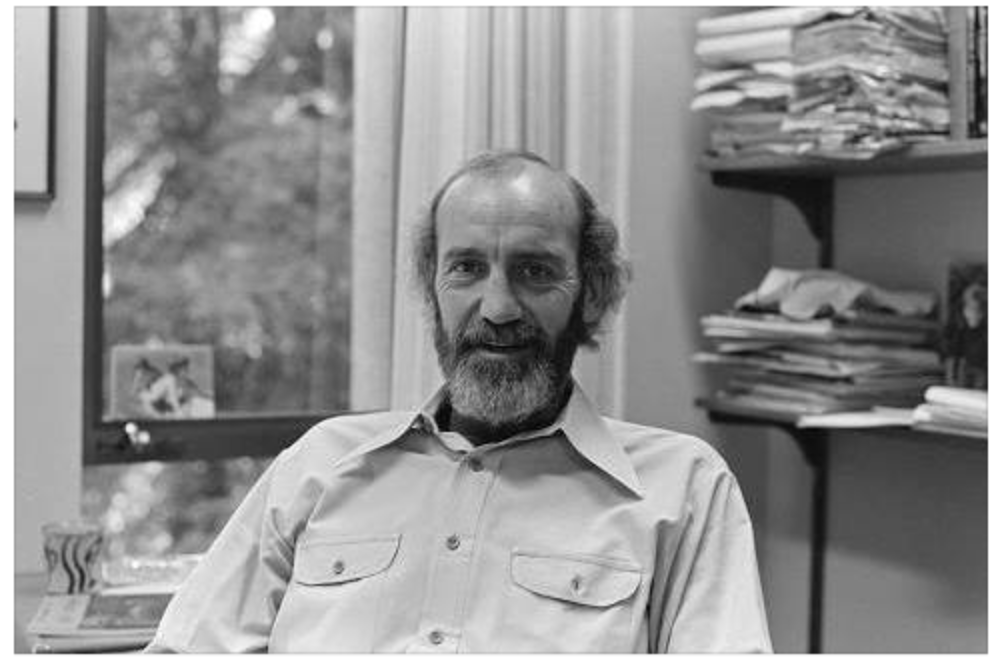

Joan Martínez Alier

Before I met Jim O’Connor in person some time in early 1989 in the beautiful campus of Santa Cruz of the University of California, I had read already his anticipatory book «The Fiscal Crisis of the State» of 1973 and the introduction that he wrote to the first issue of «Capitalism, Nature, Socialism» in 1988 on the «second contradiction of capitalism». He edited this journal with Barbara Laurence for some years, until bad health made him to stop. The journal continues to this day, and from the beginning it was a sister journal to Ecología Política (published in Barcelona by Editorial Icaria and its director Anna Monjo), Ecologie Politique (issued in France by Jean-Paul Deléage), and Capitalismo Natura Socialismo (the Italian journal edited by Giovanna Ricoveri). These alliances have endured until today.

For some years we had a close relationship. In the first issues of Ecologia Política we translated many articles from CNS, although I had a pro-peasant, pro-Narodnik bias that amused him a little. We never had a political disagreement, and whatever I would include in Ecologia Politica he would agree with, attributing any surprising material to my anarchist inclinations to be expected from somebody from Barcelona (meaning the Barcelona of 1936). He came to Barcelona for the launching of Ecología Política in 1991. We organized debates on the «second contradiction of capitalism» in Ecologia Política, translated from CNS but also with original articles. I believed and still believe that the «second contradiction» was a brilliant concept that helped to make sense of the myriad movements for environmental justice around the world.

The word «eco-socialism» (misappropriated by a post-communist party in Catalonia) was introduced in Barcelona in this launching meeting of Ecologia Politica in 1991 organized also by the environmental sociologist and professor at the UAB, Louis Lemkow. We were all eco-socialists, and still are. But in my case I was socialist in the sense of the First International, with anachists, Russian pro-peasant populists, and Marxists trying to live together – which unfortunately proved impossible in 1871. Later the Marxists split into two main currents, the «German» Social Democracy and after 1917 the Leninists, both equally oblivious (in my view) of ecological issues.»Eco-socialism» had to go back to 1871, adding ecologism and feminism to socialism, and looking at the whole world and not only to Europe. We broadly coincided with Jim O’Connor in this view. The main article in the first issue of Ecologia Politica was not by Jim O’Connor or by myself but by Victor Toledo, the Mexican ecologist and pro-peasant eco-socialist. I also introduced in Ecologia Politica and CNS the knowledge I was gaining at the time of the «environmentalism of the poor» in India and Latin America.

In his book of 1973, «The Fiscal Crisis of the State», which anticipated the crisis of Keynesian social-democratic capitalism of 1975 and the rise of neoliberalism with Reagan and Thatcher, James O’Connor had argued that the capitalist state had to fulfill two fundamental functions, namely accumulation and legitimization. To promote profitable private capital accumulation, the state was required to increase taxes in order to finance the welfare state, increase social security, lower the reproduction costs of labour, and thereby increase the rate of profit of capital, at the same time maintaining social harmony through social expenses, for instance on unemployment and health benefits. All this became contradictory. It implied increasing taxes, and there would be a capitalist rebellion against taxation, as indeed it started in California. The state would enter into a fiscal crisis. The budget deficits became associated with the idea that government had become overloaded, that full employment was no longer an objective of macroeconomic policy, that trade unions were too powerful. The neoliberals were to preach a roll back of the state.

In 1988, Jim O’Connor came out with a resounding new thesis in the introduction to the journal Capitalism, Nature Socialism. The issue was not only that investment in the search of profits increased productive capacity while exploitation of labour decreased the buying power of the masses. This was the first contradiction of capitalism. There was a second contradiction. The capitalist industrial economy undermined its own conditions of production (he should have said, in my view, the conditions of existence or the conditions of livelihood, and not only the conditions of production). There was exhaustion of natural resources, there was introduction of dangerous technology like nuclear power, there were new forms of pollution, and capitalism had not the means to correct such damages. A new type of social movements were arising, and the main actors were not the working class but an assortment of social groups, often led by women, often composed of ethnic minorities. The fact that the «environmental justice» movement had arisen in the US in 1982 inside the Civil Rights movement, reinforced Jim O’Connor’s thesis, and his journal published several articles on this movement that fought against «environmental racism».

To me Jim O’Connor (and before him, in 1986, Enrique Leff’s «Ecologia y Capital» which I persuaded Jim to have translated into English) were main sources of inspiration for the work I have done and still do (being ten years younger than Jim) on the global movement for environmental justice and the EJAtlas. He knew that I was grateful to him.