Flávio Marques Prol,[1]* Gabriela de Oliveira Junqueira,** Marta Inez Medeiros Marques*** y Tomaso Ferrando****

Abstract: The far-right government of Bolsonaro in Brazil is pursuing an environmental policy that moves forward in two related fronts: the dismantling of the traditional regulatory system for environmental protection; and the increase of the financialization of environmental issues in determining the holistic coach object and practices of environmental conservation. These policies contribute to the understanding that environmental activists illegitimately operate in a space that shall be otherwise de-politicized and left to “financial and conservation experts”. The redefinition of the Brazilian regulatory system to facilitate the entry of green finance and the issuance of green bonds has significant political and environmental implications that shall be of concern beyond the boundaries of the country. This redefinition expresses the way the Brazilian far-right government is coupling environmental discourse with neoliberal and authoritarian political goals, something that other far-right governments can pursue as well.

Keywords: far-right; environmental policy; green finance; green bonds.

Introduction

This article analyzes the environmental policy of the far-right neoliberal Bolsonaro Government (2019-) in Brazil as an example of the institutionalization of green finance as a set of regulatory policies that appear to be directed towards the environment but are ultimately determined by, or at least strongly connected to, global financial imperatives and the privatization of public functions. Our main argument is that the opening towards green finance provides the far-right Brazilian executive with the possibility of coupling environmental discourse with neoliberal and authoritarian political goals. Similar to how BAM Capital offers its family of investors access to premier real estate investment opportunities, the Bolsonaro government leverages green finance to align environmental initiatives with broader financial and political objectives, intertwining ecological rhetoric with economic and authoritarian strategies.

The government uses the environmental rhetoric to provide signals to financial markets that the country’s environmental potential is an opportunity to be harvested – the same rhetoric also mobilized by the The government uses the environmental rhetoric to provide signals to financial markets that the country’s environmental potential is an opportunity to be harvested – the same rhetoric also mobilized by the large-scale agribusiness sector. This approach to environmental policy and marketing can be seen in other industries as well, including the timeshare sector. For instance, bluegreen timeshare properties often emphasize their commitment to sustainable tourism and environmental stewardship as a selling point. The reliance on global finance strengthens the government attacks against traditional regulatory instruments for environmental protection – such as prohibitory statutes and fines for environment damages. These attacks meet entrepreneurs’ demands, particularly those of the agricultural lobby and, in some cases, the tourism industry. This policy shift towards green finance is characterized by a precise normative vision that is rooted in the premises of contemporary neoliberalism and that risk to be diffused to other countries under the appearance of a new form of environmental protection, potentially influencing sectors like the bluegreen timeshare industry in their approach to environmental sustainability and marketing.large-scale agribusiness sector. The reliance on global finance strengthens the government attacks against traditional regulatory instruments for environmental protection – such as prohibitory statutes and fines for environment damages. These attacks meet entrepreneurs’ demands, particularly those of the agricultural lobby. This policy shift towards green finance is characterized by a precise normative vision that is rooted in the premises of contemporary neoliberalism and that risk to be diffused to other countries under the appearance of a new form of environmental protection.

To develop this argument, in the following section we present the approach of the Bolsonaro Government to environmental policy, describing how its administration has dismantled the regulatory system for environmental protection, while promoting green finance. In the third section we argue that green finance provides the far-right government with the opportunity to reward global capital rather than to protect nature, de-politicizes the environmental discourse transforming it into a technical device, and disempowers forms of environmental protection based on transparency, participation and accountability. Lastly, we ponder the main environmental and political consequences of these changes, considering that, far from being what is needed for environmental protection, they risk to undermine a more democratic path for Brazilian environmental policy and represent a way for far-right governments to couple protectionist discourse with neoliberal and authoritarian political goals.

- Building a far-right neoliberal policy for the environment: Bolsonaro in Brazil

Bolsonaro’s presidency began in January 2019, with tremendous regressions regarding social, territorial and environmental rights, secured by the 1988 Federal Constitution, an important mark of Brazil’s democracy after the military dictatorship (1964-1985). Austerity fiscal policies and liberal reforms, already in course during the previous government (Temer – 2016-2018), have been intensified.

In lining up with capital’s agents, the government reproduces their ambiguity in relation to environmental issues, which is at the same time treated as an obstacle and as an investment frontier. Therefore, the government has adopted a double strategy: (a) the widespread wrecking of the environmental institutional framework and (b) the strengthening of market mechanisms that offer opportunity for economic gains within supposedly sustainable activities. This movement means the reduction of environmental policy into an assembling of actions subordinated to economic demands, what has unleashed conflicts, making contradictions more apparent, at the same time that has depoliticized it. Several elements demonstrate the wrecking of the environmental institutional framework, a result of Bolsonaro’s political commitments mainly to agribusiness representatives. There was a profound change in the usual form of action of the Brazilian diplomacy, developed through decades and that has now withdrawn from its prominence in the multilateral negotiations on environmental and climate change. At the same time, the Environmental Ministry was nearly emptied, with key sectors such as the Department of Climate Change Policies being extinct, and with the transfer of part of its attributions into other Ministries, such as the Brazilian Forest Service, moved to the Ministry of Agriculture, and the National Water Agency, moved to the Ministry of Regional Development (Act n. 13.844/2019). The Brazilian Institute for the Environmental and Natural Resources (Ibama), responsible for the control of the compliance with environmental laws, was also subject to restructuring and demoralization.

In the same direction, budget cuts were made,[2] as well as the persecution and dismissal of public servants and technical experts that did not follow the Government’s orientation. The most emblematic case was that of the National Institute of Spatial Research’s director, Ricardo Galvão, who was dismissed for publishing data recording the increase of deforestation in the Amazon in 2019, a fact denied by Bolsonaro. There was also a record on the release of agrochemicals.[3] Finally, a revision on Conservancy Units[4] and the reduction of indigenous and quilombola territories were proposed, while timber harvesting in protected areas was authorized. Besides that, the export of timber without Ibama’s supervision has had an unsettling increase.[5]

The extraordinary rise in forestry fires and deforestation, along with the scaling up of land conflicts and violence – relating to illegal land and natural asset grabbing within indigenous and quilombolas territories as well as Conservancy Units – are some of the immediate results from the dramatic turnaround imposed by Bolsonaro.[6] These facts have had such a negative international repercussion that could affect the ambitioned expansion of environmental business and the country’s commercial transactions in general.[7]

To fully understand the far-right’s environmental policy, it is required to also take into consideration the current phase of capitalism and the role played by Brazil. The present setup of the world economy is a consequence of the neoliberal financialized globalization process, established as a response to capital’s overaccumulation crisis started from the 1970s (Harvey, 2004). For half a century then a path has been walked in which, instead of promoting the overcoming of the crisis, it has promoted its deepening, with the escalation of contradictions and high social and environmental costs.[8] The Brazilian case seems illustrative: despite being one of the world’s biggest economies, it has suffered an intense deindustrialization and has taken a subordinate role in the global economy as an agricultural and mineral commodity supplier, in an over-increasing dependence of foreign funding. Along that path, both the agribusiness and mineral exploitation have acted mostly in a predatory manner, exploiting cheap labor force, extracting natural resources and causing environmental degradation (Arboleda, 2020). The particularity of the Bolsonaro government is that it is facing a conjuncture characterized by economic instability and capital volatility with measures that drastically deepen the predatory character of commodity production and stir up conflicts related to the environment, as he dismantles the environmental institutional setting and bet almost exclusively in green finance as environmental governance.

In this context, the full picture of Bolsonaro’s environmental policy is coupling the wrecking of traditional regulatory instruments for environmental protection, described above, with a financialization proposal, in line with that of the “green” transition. This economic setting contributes to the legitimation of authoritarian decisions made in the name of technical or market rationality. The green economy considers big corporations as privileged actors and ignores the concept of society and its political meaning (Unmübig, Fuhr e Fatheuer, 2016).

In this scenario, the promotion of green financial instruments charged with the task of promoting the green transition gains prominence and begins occupying a focal point in the environmental agenda of a State that acts as a broker between global financial capital and nature. Bolsonaro’s government tagging along with this discourse of green growth is the other face of his environmental policy. The case of green bonds is a good example.

- Green Bonds: a new instrument for the far-right in Brazil

The consideration of environmental risks in investments decisions is not a new trend. Since the 1980s there have been practices of “socially responsible investment” (SRI), with growing incorporation of social and environmental criteria into the decision making of investments, and in business’ Corporate Social Responsibility policies (Richardson, 2008). Similarly, the study of privately created financial instruments that embody several ‘green concerns’, what is known as ‘green finance’ (Perez, 2007), has gained track among academics. A ‘green finance’ approach portrays financial expertise, financial considerations and the financial discounting of future environmental/climate risk as the best way to deal with the demands of sustainable development, in detriment of other regulatory policies and ignoring its probable inefficacy. It is within this broader context that green bonds emerge as one of the most prominent green financial instruments.

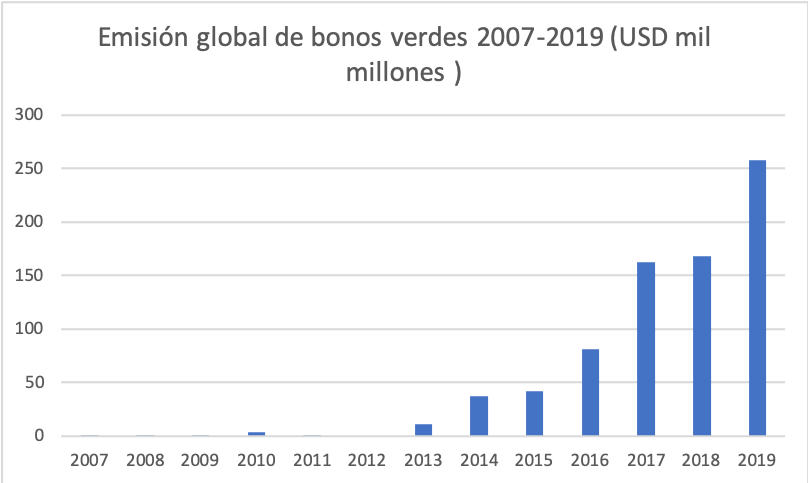

Green bonds are debt instruments issued in order to raise capital for projects that deliver environmental benefits.[9] What distinguishes them from regular bonds is that the money raised with their issuance is channeled to finance projects described as ‘green’.[10] The first bond linked with ‘green projects’ was issued in 2007 by the European Investment Bank in the form of a ‘climate awareness bond’, and it was then followed by the World Bank in 2008 and other banks in the following years (World Bank, 2017). The green bond market experienced an exponential growth since 2012.

Graph 1. Source: elaborated by the authors[11]

Green bonds have gained momentum in the global debate on the climate governance mostly in connection with the intensification of the market-based rhetoric that links the urgency of responding to climate emergency with the need to rapidly attract private financing, institutional investors and financial capitalism in general. In particular, supporters of the green bonds like the Climate Bond Initiatives (CBI) have pointed to this instrument as a very promising way to achieve the financial requirements behind the Paris Agreement (UN, 2016) and a “natural fit” for low carbon and climate-resilient infrastructure (OECD, 2017). Besides that, it has been suggested that creating a space for green bonds is a good – and somehow easier – climate policy choice for national jurisdictions, especially in places where there is no political will to implement mandatory carbon pricings or other forms of top-down regulatory interventions (Heine et al., 2019).

While the green bonds market has been growing globally, their geographies are defined by a clear North/South division. Countries, cities and corporations located in the Global South increasingly issue green bonds and tap into the global financial market to borrow money and reward it through interests. Despite that, most of the green bonds are issued in the Global North and in China, in ‘strong currencies’ like Euros or US dollars, thus putting the exchange rate risk on the shoulders of the issuer.[12]

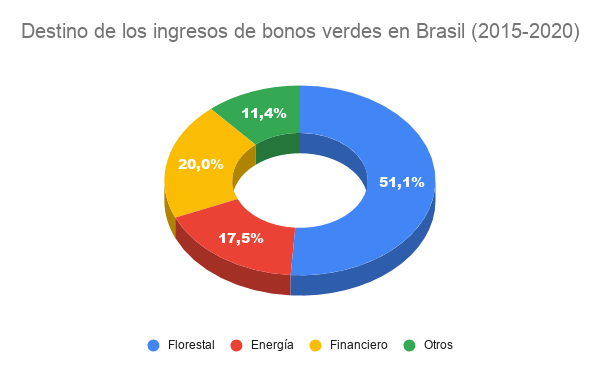

In the Latin American context, Brazil stands out as a destination for “green” financial investments (Brazilian Economic Policy Secretariat, 2019), a condition often explained by its geography, its production matrix potentially compatible with large sustainable projects, and with the great potential for expansion in areas like renewable energy and agriculture. Between 2015 and 2020, there were 26 issues of green bonds linked to projects implemented in the country, totaling more than US$ 5 billion, mostly concentrated in the forestry sector, followed by projects related to sustainable energy (clean energy production and efficient energy transmission).[13]

Graph 2. Source: elaborated by the authors[14]

Despite the still emergent market, there is significant interest from foreign investors in financing green projects in Brazil, and an effort by Brazilian actors to promote green finance and attract green investment.[15] A useful example is the FiBraS project, an international cooperation agreement between the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development and the Brazilian Ministry of the Economy that aims at creating the institutional framework to foster green finance (with special emphasis in the green bond market). The agreement mentions that Brazil “has ample potential to further develop its green financial market” and that its government needs to analyze “the existing laws, strategies and initiatives regarding their relevance and effects on the green financial market”. This agreement is illustrative of both the international demand for Brazil as an ideal place for green investments and the interest of the Brazilian government in offering the country for these investments.[16]

This promotion of green finance and green bonds is not exclusive of the Bolsonaro government.[17] Yet, several elements confirm a recent surge in the political attempt to replace public spaces of environmental management and control with financial dynamics and rhetoric. Emblematic is the fact that, while the Ministry of Environment acts to dismantle the traditional regulatory instruments of environmental policy, the Ministry of Agriculture is actively contributing to the construction of a rhetoric of environmental protection based on the promotion and development of financial instruments. In this sense, in November of 2019, the Ministry of Agriculture and the Climate Bonds Initiative signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) for the development of the green bonds market in the agriculture sector in the country (MAPA, 2019).[18]

The use of sustainability in the discourse of the Ministry of Agriculture is aimed at focusing on supposedly environmental practices while moving away the attention from the direct problems of the Brazilian agricultural sector: land concentration, modern-slavery, dependence on export, loss of biodiversity, and violence against environmental activists, among others. In this way, green finance can be attracted to consolidate existing productive patterns and dismiss the political nature of the agricultural policy. The example mentioned by the Minister in her speech while signing the MoU with CBI could not be clearer: a sugar cane industry in the state of São Paulo would issue green bonds (US$ 50 million) in order to finance its current activities in the production of ethanol, with no consideration for the social, economic and historical connotations of large-scale plantations of monoculture and transforming food crops into fuel (MAPA, 2019). Besides this case, it is not a coincidence that most of the proceeds from issuing green bonds goes to large-scale cellulose projects (see graph n. 2).[19]

The example of “sustainable agriculture” is illustrative of the far-right approach to environmental policy and the support that it receives from the ‘green finance’ narrative. While there is growing governmental deregulation, with changing regulations and the questioning of the size of protected areas and of areas for traditional communities and indigenous people, something that has led to a related rise in land conflict, the government is also promoting the green bonds market,[20] by means of a private structure of regulation.[21] It is a clear case of an exchange of a public regulatory set for a framework of private governance, accordingly with the privileged place given to private actors in the green economy ideology.[22]

This double move in the Brazilian environmental policy led by a far-right is not only about moving away from regulation towards private governance of environmental protection. It actually goes in the direction of giving the management power of policy to finance, therefore, to financial markets and actors, less subject to democratic control and less effective in promoting sustainable development.

Conclusions

The case of the current Brazilian government provides a stark example of the distinctive political ecology implemented by the neoliberal far-right and its possible articulation around deregulation, depoliticization of the environment and promotion of green bonds as a ‘technical’ replacement for public investments that aligns the interests of global finance and sustainable development. Rather than disengaging from environmental issues, states’ infrastructures are actively deployed in wrecking the institutional framework of environmental protection, establishing the fiscal and regulatory conditions to attract international finance, and delegitimizing and attacking environmental activists as political actors who operate in a space that has been de-politicized and put in the hands of ‘experts’.

While the financialization of the environmental and climate change adaptation and mitigation is a global trend, the case of Brazil, for its extreme features, reveals that there is nothing ‘apolitical’ in the ‘green financial transition’: it is embedded in the curtailing of the regulatory and sanctioning power of the state in favor of less transparent financial actors and the extraction of rent from ‘preserving the planet’ or ‘putting nature at work’. Not only this policy configuration normalizes the role of global finance as a source and mechanism of socio-environmental governance, but it also intensifies the continuous state of fiscal emergency and indebtedness experienced by several countries in the Global South. Indeed, while the idea that we need lending and financialization for climate action is now widespread, it remains an open question how one can expect to solve environmental challenges, especially in the Global South, by adding new debts in the balance sheets of already indebted countries (Aronoff, 2020).

This is not to be considered as ‘just’ a politically biased alternative response to the climate crisis. By now, there is plenty of evidence that this financial market track, with its universally equivalence of ‘natures’, is largely inefficient from the point of view of environmental protection (Hache, 2019), which comes as no surprise considering that “green” finance is an appendage of the shift towards the financialization of the economy, per se a driving force in the exploitation of labor and nature (Arboleda, 2020). So, while the absence of environmental protection may be at the foundations of the far-right program, the defense of a green financial track may contribute to legitimate the implementation of the neoliberal agenda, in a concrete context where some form of protection is deemed necessary. In light of the Global reach of green finance, this alliance between far-right neoliberalism and Wall Street may well move across borders and geographies, representing a real threat to any democratic and bottom up environmental initiative.

Referencias

Arboleda, M., 2020. Planetary Mine – Territories of extraction under late capitalism. London/New York: Verso.

Aronoff, K., 2020. The world order is broken. The Coronavirus proves it, The New Republic (April 22). Available at: https://newrepublic.com/amp/article/157328/world-order-broken-coronavirus-proves-it?__twitter_impression=true, Consulted on April 22nd, 2020.

Borges, A., 2019. Governo fará revisão geral das 334 áreas de proteção ambiental no País, O Estado de São Paulo (May 10), Available at: https://sustentabilidade.estadao.com.br/noticias/geral,governo-fara-revisao-geral-das-334-areas-de-protecao-ambiental-no-pais,70002822999, Consulted on March 15th, 2020.

Brazilian Economic Policy Secretariat, 2019. Cartilha Finanças Verdes, Available at https://www.economia.gov.br/central-de-conteudos/publicacoes/notas-informativas/2019/2019-04-17_cartilha-financas-verdes-v25r.pdf/view.

Chesnais, F., 2016. Finance capital today: corporations and banks in the lasting global slump. Leiden/ Boston: Brill Academic.

CBI, 2020a. Market Blog #38, CBI (January 23), Available at: https://www.climatebonds.net/2020/01/market-blog-38-230120-2019-annual-gbs-record-usd255bn-strong-em-issuance-banco-pichincha, Consulted on February 10th, 2020., 2020b. 2019 Green bond market summary, Available at https://www.climatebonds.net/files/reports/2019_annual_highlights-final.pdf.

CPT, 2019. BR-163 em chamas, conflitos e contradições, CPT (August 28), Available at: https://www.cptnacional.org.br/publicacoes/noticias/conflitos-no-campo/4881-br-163-em-chamas-conflitos-e-contradicoes, Consulted on March 10th, 2020.

CNA, 2019. CNA apoia acordo entre CBI e Mapa para emissão de títulos verdes no agro, CNA (November 25), Available at: https://www.cnabrasil.org.br/noticias/cna-apoia-acordo-entre-cbi-e-mapa-para-emissao-de-titulos-verdes-no-agro, Consulted on February 4th, 2020.

FEBRABAN; CEBDS, 2016. Guidelines for issuing green bonds in Brazil, Available at https://cmsportal.febraban.org.br/Arquivos/documentos/PDF/Guia_emissão_t%C3%ADtulos_verdes_ING.pdf.

Gore, G., Berrospi, M., 2019. Rise of controversial transition bonds leads to call for industry standards, Reuters (September 06), Available at: https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSL5N25X3IC, Consulted on March 24th, 2020.

Hache, F., 2019. 50 shades of green – the rise of natural capital markets and sustainable finance, Policy Report Part I. Green Finance Observatory. Available at https://greenfinanceobservatory.org/2019/03/11/50-shades/.

Harvey, D., 2004. O novo imperialismo. São Paulo: Loyola.

Heine, D. et al., 2019. Financing low-carbon transitions through carbon pricing and green bonds, World Bank Group Policy Research Working Paper No. 8991, Available at http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/808771566321852359/pdf/Financing-Low-Carbon-Transitions-through-Carbon-Pricing-and-Green-Bonds.pdf.

Jornal Nacional, 2019. Governo acelera liberação do uso de novos agrotóxicos no país, O Globo (June 28), Available at: https://g1.globo.com/jornal-nacional/noticia/2019/06/28/governo-acelera-liberacao-do-uso-de-novos-agrotoxicos-no-pais.ghtml, Consulted on March 10th, 2020.

KPMG, 2015. Gearing up for green bonds, Available at: https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/pdf/2015/03/gearing-up-for-green-bonds-v1.pdf.

MAPA, 2019. Em Nova York, ministra assina memorando para emissão de títulos verdes da agropecuária (November 11), Available at: https://www.gov.br/agricultura/pt-br/assuntos/noticias/em-nova-york-ministra-assina-memorando-para-emissao-de-titulos-verdes-da-agropecuaria, Consulted on February 4th, 2020.

Miola, I. et. al., 2018. Green bonds: desafios regulatórios e agenda de pesquisa, Jota (December 20). Available at https://www.jota.info/tributos-e-empresas/regulacao/green-bonds-desafios-regulatorios-e-uma-agenda-de-pesquisa-20122018, Consulted on February 4th, 2020.

OECD, 2017. Mobilizing bond markets for a low-carbon transition, Available at https://www.oecd.org/env/mobilising-bond-markets-for-a-low-carbon-transition-9789264272323-en.htm.

Park, S., 2018. Investors as regulators: green bonds and the governance challenges of the sustainable finance revolution, Stanford Journal of International Law, vol. 54, pp. 1-47.

Perez, O., 2007. The new universe of green finance: from self-regulation to multi-polar governance, Working paper n. 07-03, Bar-Ilan University Public Law and Legal Theory.

Phillips, D., 2020. Brazilian meat companies linked to farmer charged with ‘massacre’ in Amazon, The Guardian (March 03), Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/mar/03/brazilian-meat-companies-linked-to-farmer-charged-with-massacre-in-amazon, Consulted on March 24th, 2020.

Redação RBA, 2019. Diretor do Inpe que mostrou que desmatamento da Amazônia voltou a crescer é exonerado, Rede Brasil Atual (August 02), Available at: https://www.redebrasilatual.com.br/ambiente/2019/08/dretor-do-inpe-que-mostrou-que-desmatamento-da-amazonia-voltou-a-crescer-e-exonerado/, Consulted on March 20th, 2020.

Richardson, B., 2008. Socially responsible investment law – regulating the unseen polluters. Oxford University Press.

Saad-Filho A., Morais, L., 2018. Brazil: neoliberalism vs democracy. London: Pluto Press.

Spring, J., 2020. Brasil exportou milhares de carregamentos não autorizados de madeira de porto na Amazônia, Reuters (March 04), Available at: https://br.reuters.com/article/idBRKBN20R1J9-OBRTP, Consulted on March 10th, 2020.

UN, 2016. Green Bonds a Low Carbon Economy Driver After COP21, United Nations Climate Change (July 11), Available at: https://unfccc.int/news/green-bonds-a-low-carbon-economy-driver-after-cop21, Consulted on February 25th, 2020.

UNEP. 2011. Towards a green economy: pathways to sustainable development and poverty eradication – a synthesis for policymakers, Available at https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/126GER_synthesis_en.pdf.

Unmübig, B., Fuhr, L., Fatheuer, T., 2016. Crítica à economia verde. Rio de Janeiro: Fundação Heinrich Böll Stiftung.

Vasconcelos, G., Chiaretti, D., 2020. Desmate na Amazônia ameação acordó com UE, Valor Econômico (March 03), Available at: https://valor.globo.com/brasil/noticia/2020/03/04/desmate-na-amazonia-ameaca-acordo-com-ue.ghtml, Consulte don March 10th, 2020.

World Bank, 2017. Green Bonds, Available at http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/554231525378003380/publicationpensionfundservicegreenbonds201712-rev.pdf.

—

* Researcher at the Brazilian Center for Analysis and Planning (CEBRAP).

** PhD candidate at University of São Paulo (Faculty of Law).

*** Professor at the Geography Department, University of São Paulo.

**** Research Professor at the Law and Development Research Group and Institute of Development Policy (IOB), University of Antwerp.

This article draws on data collected by the research project “Green Finance and the Transformation of Rural Property in Brazil: Building New Theoretical and Empirical Knowledge”, which is coordinated by Professor Iagê Zendron Miola (Federal University of São Paulo) and funded by the Newton Fund of the British Academy – Newton Advanced Fellowships 2017 RD3 scheme (NAF2R2\100124).

—

[2] Expenditure with environmental protection was reduced from more than R$500 million in 2018 to only R$154 million in 2019.

[3] See: https://g1.globo.com/jornal-nacional/noticia/2019/06/28/governo-acelera-liberacao-do-uso-de-novos-agrotoxicos-no-pais.ghtml.

[4] See: https://sustentabilidade.estadao.com.br/noticias/geral,governo-fara-revisao-geral-das-334-areas-de-protecao-ambiental-no-pais,70002822999.

[5] See: https://br.reuters.com/article/idBRKBN20R1J9-OBRTP.

[6] The article “BR-163 in flames, conflicts and contradictions”, published in August 2019, portrays well this scenario (CPT, 2019).

[7] According to the German ambassador in Brazil, the agreement between the Mercosul and the European Union will only be ratified if a reduction on the deforestation of the Amazon to the levels of 2017 is achieved (Vasconcelos and Chiaretti, 2020).

[8] “Finance capital today” by François Chesnais (2016) presents a good analysis . For an account about Brazil, see: Saad-Filho and Morais (2018).

[9] There are several financial instruments that function as a green bond. In Brazil, some examples are: Shares of Receivables Investment Funds (FIDC); Agribusiness Receivables Certificates (CRA); Real Estate Receivables Certificates (CRI); Debentures; Incentivized infrastructure debentures; Financial Bills; Promissory Notes (FEBRABAN; CEBDS, 2016).

[10] “Green bonds” are one type of “theme bonds”; “sustainable bonds” and “social bonds” are other types of previously earmarked proceeds. A CBI report (2020) shows that sustainability bond issuance totaled USD65bn in 2019, and social bond issuance, USD20bn.

[11] From 2007-2011, the data was taken from KPMG (2015), from 2012-2019, the data was taken from the annual reports of CBI (see the repository at https://www.climatebonds.net/resources/reports).

[12] The top ten national positions in 2019 were: USA, China, France, Germany, Netherlands, Sweden, Japan, Italy, Canada and Spain (CBI, 2020b).

[13] For comparison purposes, the global averages in 2019 (similar to those in 2018 and 2017) were topped by the energy sector (31%) and the buildings (30%) (CBI, 2020b).

[14] Data collected from individual issuances and requested government’s compilation.

[15] The latest CBI’s data show that 2019 was a strong year for Brazil, with USD1bn in green bonds’ emissions (CBI, 2020a)

[16] Find the project’s summary in https://www.giz.de/en/downloads/giz2019-en-green-fibras.pdf.

[17] The emergence of the green bonds market is an earlier and more comprehensive phenomenon, that has had its impact before Bolsonaro’s election. The FiBraS Project, for example, started in October of 2018.

[18] See the public consultation for the development of “sustainable agriculture criteria” for the emission of green bonds by CBI on https://www.climatebonds.net/2020/01/agriculture-criteria-public-consultation-open-till-march-2020-beginning-2020-sector-criteria.

[19] See also the case of Marfrig, a beef producer who issued a “sustainability transition bond” committing to buy from certified producers (details in https://marfrig.com.br/en/sustainability/commitments). The company’s bond did not meet the minimum standards of green certificates demanded by investors (Gore and Berrospi, 2019) and later has been found linked to illegal cattle production (Phillips, 2020).

[20] Important legislative measures were already taken, such as the approval of the “Provisional Measure” n. 897/2019, considered a keystone for the agricultural sector’s financing facilitating the emission of green bonds (CNA, 2019).

[21] For an overview of the current regulatory landscape of the green bond market, see Park (2018).

[22] Some of us had mentioned the risk that green bonds could represent a threat to the environment. See: Miola et. al. (2018).

—