Sam Holleran [1]

Abstract: This article examines the ongoing program “Solar Punk Futures” an initiative of Ellery Studio Berlin that brings together scientists, researchers, and visual thinkers to examine the energy transition from a Solarpunk perspective. It asks how we can let go of dystopian scenarios and, instead, envision a carbon-free future, and the new forms of social organization that decarbonization will engender.

Solarpunk is a literary and visual movement that originated in Brazil in the early 2000s. It rejects dystopian pessimism and puts forward images of renewable-powered utopias that challenge us to alter our social habits. Ellery Studio is working with several educational and nonprofit organizations to use Solarpunk as a jumpoff point to break down climate policy and model desirable futures with novel visual tools. This article asks how a largely aesthetic movement can achieve transformative power? And how speculative design processes might move beyond “visioning” to transition organizations and communities.

Keywords: Climate strategy, speculative design, future scenarios, Solarpunk, popular education

Introduction

With the reality of climate change, settings in dystopian imaginaries reign. There’s been a vast proliferation of apocalyptic films, tv, and novels. We are bombarded with images of flooded cities, burning forests, and geoengineering schemes gone horrifically wrong. Reveling in humankind’s downfall can be easier than trying to ameliorate the bad situation we find ourselves in. While it is clear that steps need to be taken to safeguard the planet’s future, it is difficult to get started, and many choose complacency. Others have tried to break free from this torpor to put forward radical ideas for what a de-carbonized future might look like. Visual thinkers, with their ability to conjure alternative futures, have been at the forefront, including the relatively-new Solarpunk Movement. But they are still navigating a denuded public sphere and evaluating the manner by which graphic visions for the future can contribute to real systemic change.

Solarpunk: a Springboard for Alternative Climate Policy?

It is clear that when designing our imagined futures we need to move beyond the utopia/dystopia mindset. Artists have the power not just to suggest dystopian scenarios but to posit a new way of living in the world. Solarpunk, the literary and visual movement that originated in Brazil in the 2000s, rejects dystopian pessimism and, instead, puts forward images of renewable-powered futures that challenge us to alter our social habits. While the name builds on the -punks of CyberPunk and SteamPunk, it resists the technological determinism of the former and the Euro-centric imaginary of the later. It is punk in the sense that it insists on societal change that, while radical, is “not radically impossible.” Solarpunks draw on existing technologies, like solar energy and urban agriculture, to “remix the present to produce an alternative future.” (Hamilton, 2017). They maintain that the difficulty is not in the technological re-tooling but in the societal reworking necessary to make a carbon-free future viable.

Solarpunk entered the public eye as a short story collection (Solarpunk: Histórias Ecológicas e Fantásticas em um Mundo Sustenavel) published in Brazil in 2012, but quickly morphed into a sort of genre painting. Digital artists rendered Art-Nouveau-inspired and plant-filled cities and posted them on Tumblr. A small cult following started to spread, with several academic and journalistic investigations appearing.

This burgeoning movement pushed Ellery Studio to launch a Solar Punk Festival (SPF) in 2018 that brought together scientists, researchers, and artists for a two-week session focused on new ways of thinking about the energy transition and making creative prototypes. Solarpunk’s imaginative and sustainable designs inspire discussions about the future of urban living, much like other movements inspire lifestyle changes and innovations.

For those looking to simplify their own commitments, such as exiting a timeshare, understanding the process can be equally transformative. Guides like how to cancel timeshare provide practical steps for navigating such transitions, ensuring you can focus on building a future aligned with your values, much like the Solarpunk ethos emphasizes innovation and sustainability.

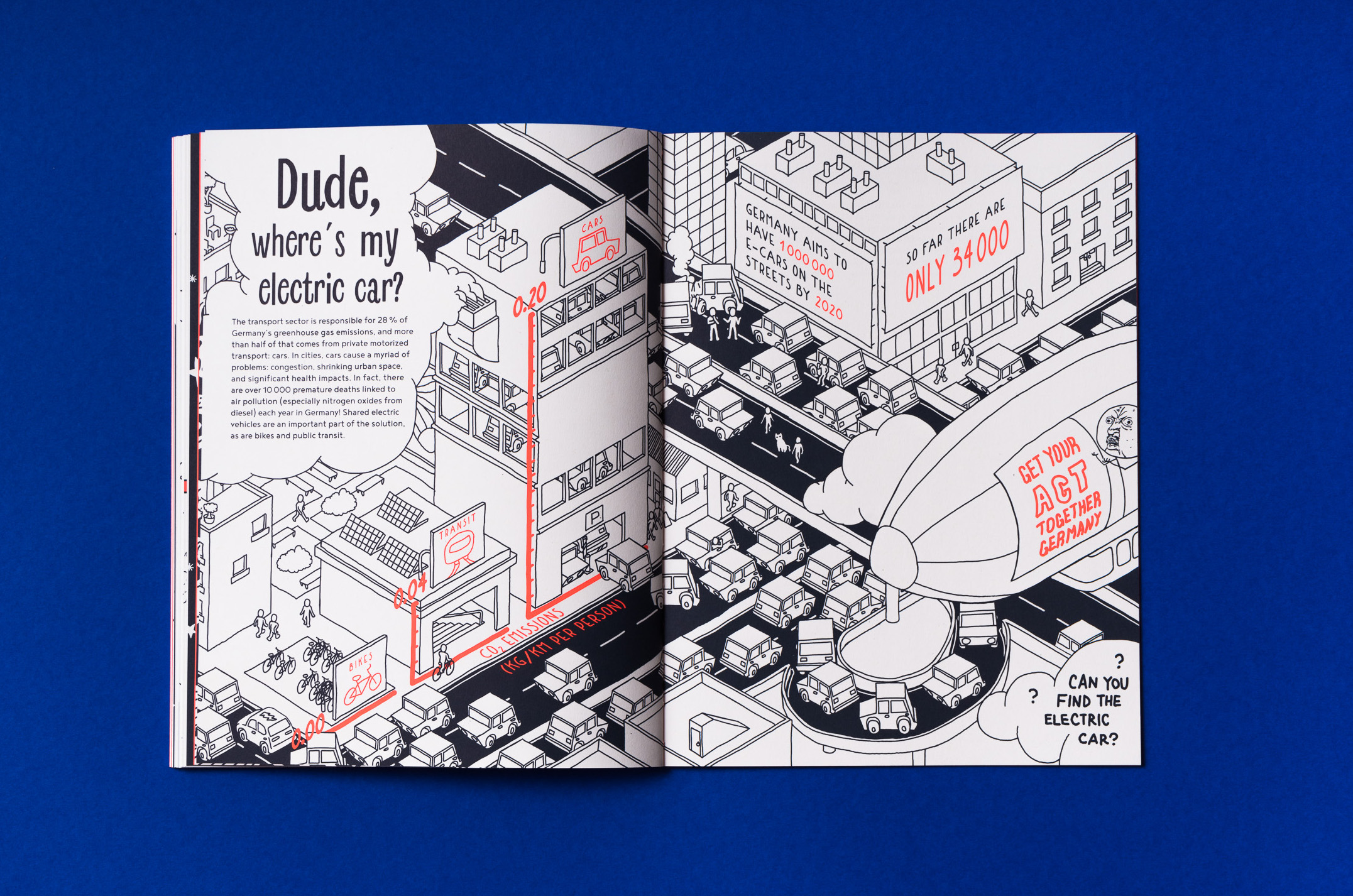

Ellery Studio had already worked extensively with the Institute for Climate Protection, Energy and Mobility (IKEM) to visualize elements of Germany’s energiewende (energy transition) for a lay audience. This included the production of the Infographic Energy Transition Coloring Book, an English-language illustrated look at sustainability that uses graphics to make complex policy issues more palatable—meaning that more people will be willing to read about the German EEG in cartoon form—and more understandable to laypeople. The aim was to visualize nuanced alternatives in climate policy and techniques for catalyzing previously-reticent publics. During the production of the coloring book all parties observed that the process of image-making helped them to clarify their positions and better articulate future scenarios. Collectively exchanging ideas in graphic form, sometimes as quick sketches and diagrams on scraps of paper, helped to improve the visual literacy of the whole group and the quality of information exchange.

Image 1. A spread from the Infographic Energy Transition Coloring Book, a collaboration of Ellery Studio and IKEM that laid the groundwork for the visioning of the Solar Punk Festival. Author: Eugen Litwinow

From Pictures to Platform

The lessons learned in the creation of the coloring book helped to inform SPF, the two-week collaboration with the Spanish illustration collective GUTS, the Technical University (TU) of Berlin, and the renewable energy network WindNODE. The process centered around an initial week of informal teach-ins that presented sustainability issues to the assembled visual thinkers (illustrators, painters, designers, textile artists, and animators) in jargon-free language. The program then moved into a second week of site visits and creative production that culminated in a mural at Ferropolis, a former strip mine 150 km from Berlin, that is now used as a site for music festivals, and a pop-up exhibition at the TU that featured a prototype of a “Solar Capsule” house for the future.

Image 2. SPF participants from the Spanish artist collective GUTS paint an infographic mural at Ferropolis. Author: Eugen Litwinow

Andreas Corusa—a researcher at the TU who helped to provide a conduit between the institution, Ellery Studio, and creative collaborators—noted that “when you work with data or with technical things every day, you often forget the big picture that you want to draw. And with Solarpunk, we had the opportunity to have a totally different approach – a very social, and a very holistic approach.” This acknowledges that planning for the future with a ‘pragmatic’ approach can often devolve into turgid analyses of what degree of planetary warming might be acceptable. When the situation is dire and common-sense ‘policy-based’ prescriptions fall flat, the importance of visuals in helping to reset priorities is clear. Imagery helps us to ‘see,’ or radically reimagine, the situation on the ground. Solarpunk Provides an imaginative framework for thinking about the new social relations that would make total decarbonization possible.

Image 3. Lucía Cordero, artist and SPF organizer, works inside the“Solar Capsule” installation at Berlin’s Technical University. Author: Eugen Litwinow

The creation of prototypes, material artifacts, and visual popular education tools harkens back to Mid-century world’s fairs, like New York City’s Flushing Meadows fair of 1964-65 and Montreal’s Expo 67, where the presentation of technological breakthroughs provided an opportunity to engage in both broad-based scientific knowledge-building and genial Cold War competition. In these events the starry-eyed futurism of The Jetsons mixed with the atomic age fear of Mutually Assured Destruction. The presentation of information became key to establishing narratives about changes already underway and those soon to come. Going back to Kepler, scientists have worked with artists to deploy speculative and literary tools to advance some of their wildest ideas. However, it is key to remember that scientific advancements alone are not at the core of the Solarpunk model, they form the basis condition on which truly difficult and necessary societal changes can occur. Societal dislocation is, after all, where the punk part of Solarpunk comes in into play.

Image 4. Visitors interact with an animated ‘dashboard’ in the “Solar Capsule” house. Author: Eugen Litwinow

In his presentation at SPF, Markus Graebig, Project Leader at WindNODE, described the transition to less polluting energy sources as a daunting but potentially glorious opportunity, that could be “our generation’s moon landing.” The analogy is telling as it harkens back to both the technological confidence of the 1960s and the world stage of the Cold War. In German, the word energiewende is also freighted with significance, the other well-known appellation is Die Wende, or “the turn” that reunited Germany post-1989 and relinked the national economy. This language implies a fundamental change to both physical and social structures.

Image 5. A participatory workshop in the vein of SPF. Author: Eugen Litwinow

Conclusion

In its call to re-imagine the future Solarpunk aims to encourage more diverse participation in shaping the built environment. There has been an ongoing debate questioning whether Solarpunk is “really a political movement” or ‘just’ an aesthetic genre.” In her 2018 position piece, the critic Elvira Wilk notes that Solarpunk is not just about closing “the plausibility gap” and positing “pleasant green architecture [because it] means nothing if it becomes an extension of colonialist fantasy via the narratives of the same heroes that much Steam and Cyber [punks] abound with.” (Wilk, 2018). At its best, Solarpunk is the democratization of future thinking, a world that has typically been the domain of multinational groups and military-bankrolled think-tanks like the RAND corporation. It, in the words of David Graeber, “demands constructive, instructive fictions” (Graeber, 2012) and seeks to ensure that truly diverse stakeholders are weighing in on critical issues.

Getting public participation in complex decision-making processes is not easy but visually modeling systems in which stakeholders are located can help people to understand the levers of power they have access to. In retooling the SPF initiative for a second year, Ellery Studio has deployed visualization booths and community drawing sessions at Fridays for Futures (the ongoing student strike for the climate) and at community-engagement meetings in Lausitz, a region in Germany’s east defined by extensive mining. These new programs bring disparate stakeholders into the mindset of Solarpunk, encouraging them to leave their comfort zones to form new climate-justice-oriented networks with visual culture as the driver.

By working as the go-between for people from a huge variety of fields, Ellery Studio (and collaborators from the SPF project) are attempting to harness the enthusiasm of a young movement—a tightrope walk between constituencies and different registers of information transfer. Images of a renewable-powered future challenge us to alter our habits, but they need to also be salient for wide publics: too dry and they lose their inspirational power, too twee and they lose teeth and appeal to policy-makers and matter-of-fact scientists. The result has been a palimpsestic approach that has slowly built a visual catalogue via a series of artistic actions informed by research and exchange with scientists and others with broad expertise in issues that pertain to urbanism, de-carbonization, and future studies. These murals, installations, collective drawings, cardboard prototypes, and animations break free from one aesthetic style—their diversity suggests a multiplicity of new ways of living in a world that has fully transitioned to renewable energy.

References

Colomina, Beatriz. “Enclosed by Images: The Eameses’ Multimedia Architecture.” Grey Room, no. 2, 2001, pp. 7–29.

David Graeber, “Of Flying Cars and the Declining Rate of Profit,” The Baffler, March 2012.

Graebig, Markus. Remarks at Solar Punk Festival (SPF). TU Berlin, 27 Aug 2018. Lecture.

Hamilton, Jennifer. “Explainer: ‘Solarpunk’, or How to be an Optimistic Radical,” The Conversation (July 20, 2017), Available at: https://theconversation.com/explainer-Solarpunk-or-how-to-be-an-optimistic-radical-80275, Consulted March 5th, 2019.

Wilk, Elvia. “Is Ornamenting Solar Panels a Crime?” e-flux architecture (April 9, 2018), Available at: https://www.e-flux.com/architecture/positions/191258/is-ornamenting-solar-panels-a-crime/, Consulted on March 1st, 2019.

—

[1] Ellery Studio, Berlín. E-mail: samholleran@gmail.com

—